Lead poisoning and trade associations

By Sophia Abrahamson

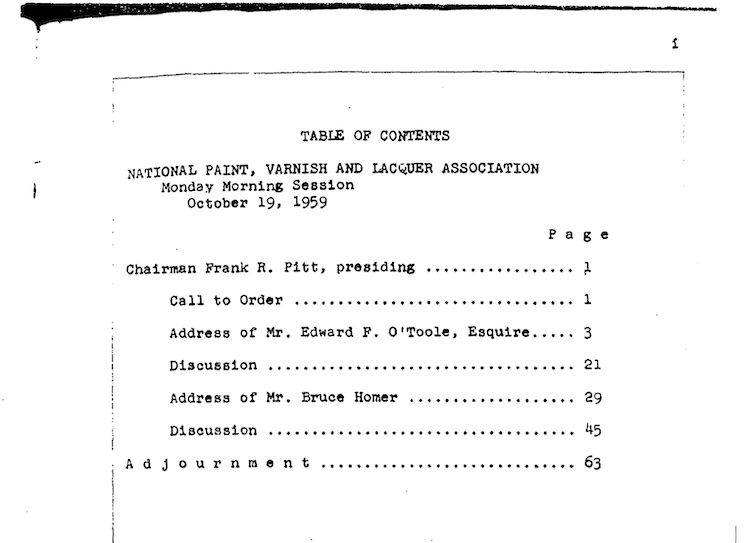

As scientists stumbled upon cheaper, more effective chemicals throughout the 20th century, lead increasingly appeared in daily products. Lead poisoning became a risk of the general public, and not just specialists working in industry (i.e., manufacturing workers, painters). Tetraethyl lead in gasoline, for example, caught the attention of experts, and documents show the Surgeon General and state governments responding to its amorphous threat. With regard to public awareness, newspaper clippings from the 1940s and 1950s note the occasional child suffering from lead poisoning. Cribs, furniture, and walls were viewed with increased skepticism. Who to blame also became a debate. The Washington Post article from 1949 entitled “Crib Gnawing Called Rare in Satisfied Child; Habit Seldom Cause for Alarm, Parents Told” points a finger at the parents––citing parental neglect, improper care, and malnourishment as primary causes. Another article with the headline “Teething Child May Be in Danger” written by Dr. Glen Shepherd in 1952 explicitly berates parents with the shocking opening line: “Your teething child can die or be permanently injured by an insidious disease you parents can prevent entirely.” It was in the context of this growing national debate that the National Paint, Varnish, and Lacquer Association convened its members in 1959 to discuss, among other subjects, their concerns of the public’s perception of lead-infused paint.

The published meeting segment on Toxic Docs highlights the portion of the Convention where the group’s General Counsel, Daniel Ring, summarizes the Association’s position, actions, and reactions to this leaden public health issue. He addresses his audience with ease and in a casual nature. His speech largely focuses on manipulating public perception: to avoid the perception that paint is bad and to instead take the offensive and reinforce blame on community (societal and familial) practices. In accordance with the newspaper clippings noted above, Ring commends newspaper articles that “[stress] the need for parents to keep their children from eating lime, plaster and flaking paint in old houses,” stating, “That's what we want.” For any sources not in compliance with his message, the Association “sent out whenever we've noticed any flare-up of publicity a statement to public health authorities.” This response is quite notable, especially given this Association’s consistency. Today, the National Paint, Varnish, and Lacquer Association goes by a different name––American Coatings Association––but their public-facing persona remains the same. In 2010, the Association complained to the Environmental Protection Agency, among others, about a Public Service Announcement that they felt suggested to viewers that paint, itself, was bad.

This Toxic Docs document further reveals how little blame the Association accepts, even within their own meetings. Outwardly, they blame the communities––consumers of their products. Within the document, they plead ignorance and blame the raw materials suppliers. Ring admits that he knows “my company makes a paint now with — there are 31 ingredients in it, and I will be absolutely frank with you, I don't know what 14 of them are.” After exclaiming “they may be poison or not,” he jokes how paint companies would need to ask for a full write up––chemical composition, toxicity, and antidotes––from their raw material suppliers these days. This admittedly convoluted statement in the text is met with “(Laughter),” which indicates some communal agreement in jest about the ignorance of the paint companies and useless exercise for the raw material suppliers to dole out a toxicology report on every chemical.

On an unrelated note, I found it personally interesting to see where in the document words were crossed out in pen ink and additional handwritten edits were made. Although most comments aimed to remedy sentence structure and other housekeeping edits, one particular correction stood out: a strikeout of the word “damn”––not typical for formal vernacular––in the phrase, “we were finding that every damn questionable childhood fatality was being laid to lead poisoning without proper diagnosis.” That this document was corrected post-printing might demonstrate some awareness that an audience might be privy to these documents, and if so, that the script should appear more appropriate for public consumption.